Susannah Fiennes

ARTIST

Hong Kong Tatler

Hong Kong, July 1994

Journalist Jane Norrie

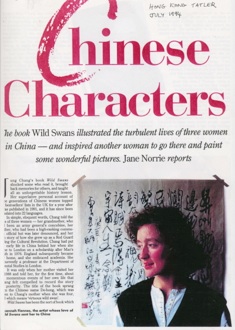

The book Wild Swans illustrated the turbulent lives of three women in China – and inspired another woman to go there and paint some wonderful pictures. Jane Norrie reports.

The book Wild Swans illustrated the turbulent lives of three women in China – and inspired another woman to go there and paint some wonderful pictures. Jane Norrie reports.

Jung Chang’s book Wild Swans shocked some who read it, brought back memories for others, and taught all an unforgettable history lesson. Her superlative personal account of the generations of Chinese women topped the best-sellers’ lists in the UK for a year after it was published in 1991, and it has since been translated into 22 languages.

In simple, eloquent words, Chang told the stories of three women – her grandmother, who had been an army general’s concubine, her mother, who had been a high-ranking community official but was later denounced, and her own story of how she grew up as a Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution. Chang had put her early life in China behind her when she came to London on a scholarships after Mao’s death in 1976. England subsequently became home and she embraced academia. She is currently a professor at the Department of Environmetnal Studies in London.

It was only when her mother visited her in 1988 and told her, for the first time, about the momentous events of her own life, that Chang felt compelled to record the story for posterity. The title of the book sprang from the Chinese name De-hong, which was given to Chang’s mother when she was found, and which means ‘virtuous wild swan’.

Wild Swans has been the sort of book which changes lives. Chang has received a host of letters, in particular from teachers and photographers, for whom the book has acted as a catalyst, compelling them to see China for themselves. One of the millions touched by this story was a British woman named Susannah Fiennes, who was inspired to use her own particular talent, painting, to depict the people of China as Chang had done through her writing.

Last year, Fiennes entered the travel section of the prestigious BP Portrait Award Competition, which is run by the National Portrait Gallery in London. She won £2,000 which enabled her to spend two months travelling and painting portraits in China, and the fruits of the resulting journey are on view until September at the National Portrait Gallery, as part of this year’s award exhibition.

Fiennes’ work rebels against the current trend for minimal and conceptual art. Since she completed her training at the Slade art college in London 10 years ago, Fiennes, 33, has concentrated on landscape and the human figure subjects which drew her to art in the first place. She spent a winter as an artist-in-residence with Hambros in New York, painting the Manhattan skyline. She is currently one of a small but promising group of young painters exhibited by the Cadogan Contemporary Gallery in South Kensington.

It was the family element in the novel which appealed to this British artist. “It’s a tale of terrible suffering, but I was inspired by the way the women came through it because of the bond in the family,” says Fiennes. “I felt that was what held them together. And I felt in tune with the way Jung Chang had been brought up. As the child of high officials, she had a privileged upbringing but she was never allowed to take things for granted – she had to have a sense of responsibility. That corresponds to the attitudes encouraged by own education at Marlborough College, and I appreciated it in Jung Chang. Her mother also moved me enormously. She came over as such a strong person, so full of character.”

In competing for the award, Fiennes not only had to submit a portrait – an oil painting of a friend’s mother – she also had to write an essay explaining her reasons for wishing to visit China. At her interview she explained how she wanted to see the country at a time of extraordinary change. “I was so moved by the suffering the people had endured, I wanted to see how their history was revealed physically,” she says.

Once she knew that she had been given the award, Fiennes wrote to Jung Chang to tell her how inspirational she had found Wild Swans, and to ask Chang if she could put her in touch with any friends in China whom she might paint. The author went one better. Her mother, Bao Qin, the middle character in the book, was again on holiday in England, and Fiennes was asked to paint her portrait.

“I was so nervous,” recalls Fiennes. “I never expected to meet such heroic people, people I had put on a pedestal. It was really thrilling. Jung Chang’s mother can’t speak English, but she comes over as a very warm, engaging person, with a great sparkle and sense of humour. Over the five mornings I painted her, we were often laughing out loud.”

Bao Qin was a revolutionary under Mao, and was married to a man who was dedicated to the ideals of communism. She endured tremendous hardship, first in the struggle to establish communism, and later in the years of the Cultural Revolution, when she was denounced, imprisoned and exiled to the countryside. She has survived the staggering upheavals of her life with great resilience and courage. “Everything is there in her face,” observes Fiennes. “It is beautiful because it is filled with character.”

Last November, Fiennes flew to Beijing and stayed in China for three months. She covered thousands of miles by plane, train and bus, staying in both the capital and Shanghai, and making extended visits further afield to Chengdu, where Chang was brought up, and to some of the most remote and inaccessible parts of the Chinese countryside.

To an artist’s eyes, China is visually thrilling. “What excited me most was the calligraphy,” remembers Fiennes. “It was everywhere -on the signposts, in huge writing on the bridges – like a series of abstract pictures. It seeped into me and, more than anything else, it has unexpectedly influenced the way I’m painting now, filling my work with an intuitive energy. I was also mesmerised by the bicycles. Moving silently, in rows five deep in Beijing, it was wonderful to see them, primal shapes like pyramids culminating in the head of the rider. Piled high with cabbages or chairs or even towing another bike behind, they seemed to strike a fundamental chord.”

As Fiennes had hoped, she was able to record Beijing in the throes of change, with the older houses or hutongs, built round traditional courtyards, being jostled by high-rise hotels. “Colour symbolises Beijing for me, with the whole effect like a Brueghel painting: the old laid out in dusty earthy greys, browns and blacks, the new in the brightest of primaries,” she says.

Fiennes had useful contacts in the artistic community in Beijing. “I painted the artist Fang Ligun and also the famous art critic Li Xianting, who curated the Chinese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. At the Hangzhou Academy I met some delightful students and discovered that my tutor from the Slade, Euan Uglow, had been there a few years ago on a British Council teaching fellowship. We had a lot in common.”

The talented English woman spent her time in such places as Shanghai and Jinghong, sitting on the streets and drawing the streams of passers-by. She was fascinated by the teeming activity, and by the fact that so many everyday tasks, such as cooking and hair washing, were done in public. Her visit to Chengdu was particularly poignant: she saw Chang’s mother again, met the author’s sister for the first time, and was able to see the scenes of their childhood for herself. One of her most prized painting is a portrait of a teacher of Western literature from the University of Sichuan, who acted as her interpreter on that day.

Among her many expeditions to see the changing face of the countryside was the rail journey from Chengdu to Jumming – 24 hours spent marvelling at the drama of the landscape. “It is one of the great train journeys of China, a wonderful vista of mountains, tunnels and gorges,” declares the artist. From Kunming, she embarked on a 12-hour bus journey to Dali, where she painted Lake Erhai, which stretches for 30 kilometres across the plain. “It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been to, simply astonishing. I was transfixed.”

In all these places she painted extensively, responding to the diversity of the landscape. With their crops of rice, tobacco, maize and beans, the terraced farmlands and the spectacular views impressed her. “Compared to the relative emptiness of the English countryside, there were so many people,” says Fiennes. “Every time I started to paint in a paddy field, I would be surrounded.”

In these remote regions, she also painted some of China’s minority peoples, whose strong ethnic identities are symbolised by their traditional dress. In Dali, for instance, she painted the Bai whose women habitually don superb pink velvet waistcoats, and in Jinghong, she depicted the Dai who wore triangular turbans and sarong skirts. In Lijian she painted the Naxis who wear blue dresses with crossover straps for carrying loads on their backs; the women, unusual for China are notorious for dominating their men.

Her return journey via Hong Kong, with its skyscrapers and smart cars, brought another culture shock. “Coming from Guilin I enjoyed the contrast of the man-made intrusions of buildings with the natural local stone ones, and from Jardine House I was to paint some spectacular views of Hong Kong harbour,” she says.

When, at last, Fiennes returned to London, it was with a mountain of sketchbooks spilling out myriad drawings and watercolours. “It’s been a totally unforgettable experience,” she says of her China wanderings. “I’ve had a glimpse of China and its people at a turning point in its history, I’ve an abundance of vital images stored up inside me waiting to be unlocked in a series of larger oils.”

In addition to providing a visual and emotive trip the visit proved to be a spur her methods of working.” … need to catch so many people and objects as quickly as possible .has liberated my work making it much more fluid and spontaneous,” she explains. “For the first time I have painted portraits in watercolour, not oil, and have experimented with other media such as gouache and pastel.”

The results of her far-flung travels have been on display since June. Taking pride of place is the portrait of Bao Qin whose story is at the heart of Wild Swans and the exhibition.

One work of art, a pocket book, has generated …a vibrant body of painting. In the process, a chai… understanding between …and West has been set… which is a source of much pleasure for….Chang herself. “I wrote Wild Swans primarily to tell my mother’s story,” says the author. “But the book also makes China more im…ate, it acts a brdige. Susannah is the only painter I know of who has gone to China as a result of reading Wild Swans and of course I’m thrilled by that.”

Chang has a special reason to feel…about her mother’s portrait. “My mother was very pleased to be painted. What I am delighted about is this – because my mother doesn’t speak English, she doesn’t get the same …as I do for the way Wild Swans has been received. Through Susannah, and through her painting, my mother could feel how the power of her stories was understood by readers all over the world. It was most wonderful to me to see the pleasure my mother received.”